The Catholic Church's Historical Teaching on Inflation: Part 1

Sacred Scripture

Hello friends! We’ve been researching and writing our Catholic series on inflation and Bitcoin—titled, Inflation, Bitcoin & the Care of Souls. The second post reviews historical Church teaching on inflation. Below, I’ve shared the first of its three parts: what Sacred Scripture—as interpreted by the Magisterium and Fathers and Doctors of the Church—teaches. Enjoy!

The Church’s Historical Teaching on Inflation

Let’s review what the Catholic Church has taught about inflation.

I will expand the research of Prof. Dr. Guido Hülsmann that prefaces his 2008 book, The Ethics of Money Production. He is professor of economics at the University of Angers and a corresponding member of the Pontifical Academy for Life.

Definition of inflation

We need a working definition of inflation to start. Here’s Prof. Hülsmann:

We can define [inflation] as an extension of the nominal quantity of any medium of exchange beyond the quantity that would have been produced on the free market. This definition corresponds by and large to the way inflation had been understood until World War II.1

Simplifying:

Inflation can also be called a forcible way of increasing the money supply, as distinct from the “natural” production of money through mining and minting. This was also the original meaning of the word, which stems from the Latin verb inflare (to blow up).2

Present day, most people mean by inflation a lasting increase of the price level, an effect that begs the question: what caused it? This ambiguity makes the modern definition often less useful than an alternative. We will study the classic definition: the forcible increase of the money supply—one clear cause of a lasting increase in the price level, among other effects it causes.

Context on Christian inflation doctrine

Prof. Hülsmann notes that the Christian treatment of this subject is relatively light:

There are very detailed statements of Christian doctrine when it comes to the morals of acquiring and using money; for example, the Christian literature on usury and on the ethics of seeking money for money’s sake is legendary. But important though these problems may be, they are only remotely connected to the moral and cultural aspects of the production of money, and especially to the modern conditions under which this production takes place. Here we face a wide gap.3

What we will study is therefore to be treasured!

Three eras of teaching

We can divide his review of the Church’s teaching into three eras: Sacred Scripture, diverse 12th-14th century teachings, and 19th-21st century encyclicals.

Sacred Scripture

First “era”: Sacred Scripture, as interpreted by the Magisterium and the Fathers and Doctors of the Church.

Leviticus 19, 35-36

Our first building block is directly from God in Leviticus 19 regarding stealing using the monetary system of the time:

35 Do not any unjust thing in judgment, in rule, in weight, or in measure.

36 Let the balance be just, and the weights equal, the bushel just, and the sextary equal. I am the Lord your God, that brought you out of the land of Egypt.

It is the last ordinance of the chapter, which ends in the next verse:

37 Keep all my precepts, and all my judgments, and do them. I am the Lord.

The Book of Leviticus is set at the base of Mount Sinai at the Israelite camp in the wilderness. It is the second year after the Exodus. Moses has received and shared the Ten Commandments and the tabernacle has been constructed. God now provides Moses detailed instructions to sustain the covenant community on their journey toward the Promised Land. We presume the location to be the tabernacle of the testimony because of Leviticus 1, 1:

1 And the Lord called Moses, *and spoke to him from the tabernacle of the testimony, saying:

The “Holiness Laws” of Leviticus chapters 17-26 are derived from its central and frequent refrain, which appears in verse 2 of chapter 19: “Be ye holy, because I, the Lord your God, am holy.” Our verses 35 and 36 contain elements of the Moral Law and Judicial Law categories of the Old Covenant. The moral remains binding on Christians—justice is eternal. The judicial is not binding—using the specific monetary tools of the time is not required today.

In verse 36, we read about balances and weights first. This pair of monetary tools accompanied pure metal money in Old Testament northeastern Africa, that is, the Egyptian empire under which the Israelites were slaves. Note that standardized coinage was not used; pure metal, often silver, or gold, was the medium exchanged. Here’s how the system worked.

The weights. These weights, often stone or bronze, were official standardized units.

The balance scale. The pure metal (the payment) was placed on one pan, and the standardized weights were placed on the other until the scale balanced.

There were many ways to steal in this system—the most common was differing weights. A dishonest person would have two bags of weights: a slightly heavier set used when buying goods (to force the seller to give more silver) and a slightly lighter set used when selling goods (to give less silver than required). Another common way was to have the balance itself tilt to one side. “Let the balance be just, and the weights equal” thus forbids stealing with the tools of the monetary system.

Catechism of Pope St. Pius X on the 7th Commandment

Indeed, the Magisterium teaches that what we’ve read is a form of stealing, and an advanced form: fraud. Pope St. Pius X in his Catechism on the Seventh Commandment—Thou shalt not steal—informs us:

9 Q. Is it only by theft and robbery that another can be injured in his property?

A. He can also be injured by fraud, usury, and any other act of injustice directed against his goods.

10 Q. How is fraud committed?

A. Fraud is committed in trade by deceiving another by false weight, measure and money or by bad goods; by falsifying writings and documents; in short, by deceit in buying and selling or in contracts in general, as well as by refusing to pay what is just and agreed upon.4

Other mentions of this teaching in Scripture

This teaching with these specific monetary tools is repeated nine more times5:

Deuteronomy 25, 13-16

Proverbs 11, 1

Proverbs 16, 11

Proverbs 20, 10, 23

Sirach 42, 4

Hosea 12, 7

Amos 8, 5

Micah 6, 11

Ezekiel 45, 10-11

The most concise reference is Proverbs 11, 1:

1 A deceitful balance* is an abomination before the Lord: and a just weight is his will.

Micah 6

The most dramatic reference is Micah 6, specifically verses 10-12. The setting is a covenant lawsuit in the mountains and hills of Judah. I’ll summarize Rev. George Leo Haydock’s commentary on the 16-verse chapter, who references the Fathers and Doctors of the Church throughout his work. The prophet Micah begins speaking, acting as divine messenger, sharing that God summons the entire natural world to witness His legal case against His people:

1 Hear ye what the Lord saith: Arise, contend thou in judgment against the mountains, and let the hills hear thy voice.

2 Let the mountains hear the judgment of the Lord, and the strong foundations of the earth: for the Lord will enter into judgment with his people, and he will plead against Israel.

In verses 3-5, God speaks directly, reviewing His unwavering fidelity:

3 *O my people, what have I done to thee, or in what have I molested thee? answer thou me.

4 For I brought thee up out of the land of Egypt, and delivered thee out of the house of slaves: and I sent before thy face Moses, and Aaron, and Mary?

5 *O my people, remember, I pray thee, what Balach, the king of Moab, purposed: and what Balaam, the son of Beor, answered him, from Setim to Galgal, that thou mightest know the justices of the Lord.

Verses 6-7 are “spoken in the person of the people”: they desire to be informed what they are to do to please God. They ask Micah:

6 What shall I offer to the Lord that is worthy? wherewith shall I kneel before the high God? shall I offer holocausts unto him, and calves of a year old?

7 May the Lord be appeased with thousands of rams, or with many thousands of fat he-goats? shall I give my first-born for my wickedness, the fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?

In verse 8, Micah delivers the Lord’s requirement: God wants justice, mercy, and humility. This is one of the most quoted verses of the Old Testament.

8 I will shew thee, O man, what is good, and what the Lord requireth of thee: *Verily, to do judgment, and to love mercy, and to walk solicitous with thy God.

Micah continues in verse 9, then God closes the case. First, He asks the people pay attention to His message of judgment:

9 The voice of the Lord crieth to the city, and salvation shall be to them that fear thy name: hear, O ye tribes, and who shall approve it?

Next, He delivers His verdict. The first charge He shares is fraud using tools of the monetary system in verses 10-12 (bolded mine):

10 As yet there is a fire in the house of the wicked, the treasures of iniquity, and a scant measure full of wrath.

11 Shall I justify wicked balances, and the deceitful weights of the bag?

12 By which her rich men were filled with iniquity, and the inhabitants thereof have spoken lies, and their tongue was deceitful in their mouth.

A “scant measure” is a tool for monetary fraud for goods gathered but not weighed before exchange, like grain. The “wicked balances, and the deceitful weights of the bag” are what we studied in Leviticus. In verse 12, the Lord says rich men misused these tools and that the ill-gotten treasures and tools remain in their possession. On verse 10, Rev. Haydock’s commentary references, “Full of wrath, &c. That is, highly provoking in the sight of God” from Vicar Apostolic Richard Challoner and “False weights are often condemned” from Abbot Antoine Augustin Calmet.6

The Lord presents His just punishments and loving discipline in verses 13-16:

13 And I therefore began to strike thee with desolation for thy sins.

14 Thou shalt eat, but shalt not be filled: and thy humiliation shall be in the midst of thee: and thou shalt take hold, but shalt not save: and those whom thou shalt save, I will give up to the sword.

15 *Thou shalt sow, but shalt not reap: thou shalt tread the olives, but shalt not be anointed with the oil: and the new wine, but shalt not drink the wine.

16 For thou hast kept the statutes of Amri, and all the works of the house of Achab: and thou hast walked according to their wills, that I should make thee a desolation, and the inhabitants thereof a hissing, and you shall bear the reproach of my people.

Some of these match today’s inflation outcomes—we will revisit later.

The Lord’s mention of deception in Micah 6, 12

Note that the Lord shares that the people of the city have fostered falsehood:

12 By which her rich men were filled with iniquity, and the inhabitants thereof have spoken lies, and their tongue was deceitful in their mouth.

This cultural mention is notable because deception is what makes these offenses fraud, as we saw in Pope St. Pius X’s Catechism. We will explore more when we study inflation culture.

To conclude our study of Micah 6, let us meditate that our All-Knowing God did not need this legal process to discern the truth of the offenses. Yet he presented the drama, using His servant Micah, teaching our spiritual ancestors and recording it in canon for our benefit.

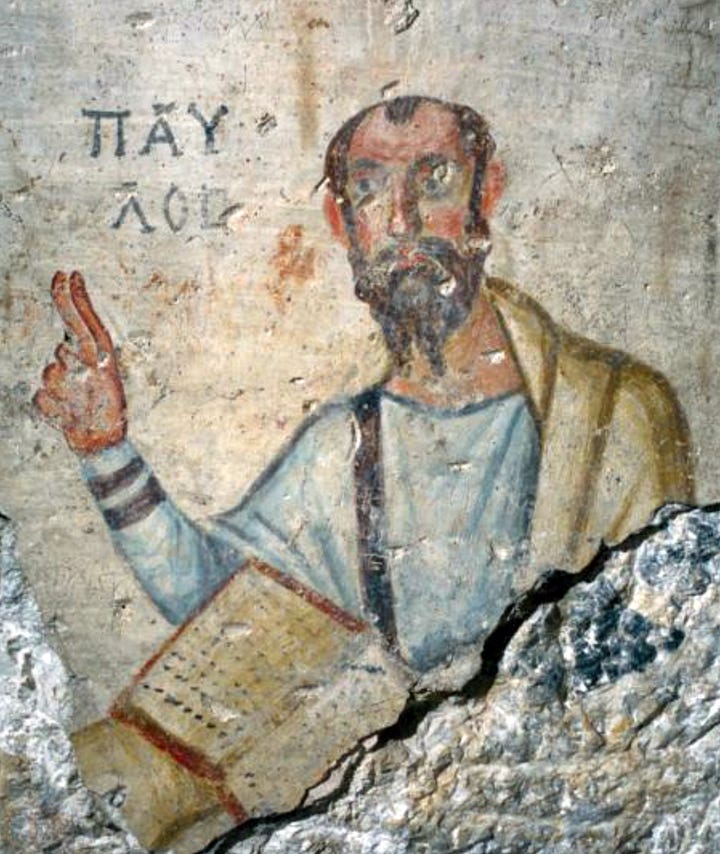

St. Paul in Romans 13

We’ll wrap up with a teaching from the New Testament that anticipates the temptation to steal with the tools of the monetary system. St. Paul commends to us the state of owing “no man any thing”—including but not limited to financial debt—in his letter to the Romans. He wrote it from Corinth near the end of his third missionary journey, around AD 57, addressing it in Romans 1, 7: “To all that are at Rome, the beloved of God, called to be saints.” The recipient was the Christian church in Rome. St. Paul gives this advice amidst social and religious tensions in the city, which we find in Romans 13, 7-8:

7 *Render, therefore, to all their dues: tribute, to whom tribute is due: custom, to whom custom: fear, to whom fear: honour, to whom honour.

8 Owe no man any thing, but to love one another: for he that loveth his neighbour, hath fulfilled the law.

The Greek word for “owe” that St. Paul uses is general. The verb, opheilo, can mean to be in debt (financially), to be bound by duty or necessity (morally or legally), and to be obligated or ought to do something. Thus while St. Paul’s advice covers State-related debts from verse 7, it also covers voluntary financial debts. The financial use is confirmed in Matthew 18, 28:

28 But when that servant was gone out, he found one of his fellow-servants that owed him a hundred pence:

And Luke 7, 41:

41 A certain creditor had two debtors; the one who owed five hundred pence, and the other fifty.

In this financial sense, the instruction is to settle outstanding financial debts promptly. It does not forbid taking on financial debt, as we can infer from the presence of the other forms of debt in verse 7, but instructs one to work towards the goal of paying off that debt and thus regaining the state of owing “no man any thing”. It follows that one should not voluntarily take on excessive debt that is challenging to repay. This advice is relevant to us because borrowing often precedes or even itself is a forcible increase of the money supply, as we will see later.

St. Paul brings the debt discussion to its conclusion in Christ’s message:

8 Owe no man any thing, but to love one another: for he that loveth his neighbour, hath fulfilled the law.

St. John Chrysostom in his Homily 23 on Romans reminds us that love is indeed the one unavoidable and eternal debt:

… “Owe no man any thing, but to love one another.” … this is a debt also, not however such as the tribute or the custom, but a continuous one. For he does not wish it ever to be paid off, or rather he would have it always rendered, yet never fully so, but to be always owing. For this is the character of the debt, that one keeps giving and owing always. Having said then how he ought to love, he also shows the gain of it, saying, “For he that loveth his neighbour hath fulfilled the law.” And do not, pray, consider even this a favor; for this too is a debt. For you owe love to your brother, through your spiritual relationship. And not for this only, but also because we are members one of another. And if love leave us, the whole body is rent in pieces. Love therefore your brother. For if from his friendship you gain so much as to fulfil the whole Law, you owe him love as being benefited by him.7

Learn more about inflation and Bitcoin

We’re excited to share more with you soon. Subscribe to be notified when a preview of part 2—featuring 12th-century Papal statements—goes live.

Jörg Guido Hülsmann, The Ethics of Money Production (Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2008), 85.

Hülsmann, Ethics of Money Production, 86.

Hülsmann, Ethics of Money Production, 2.

Pope Pius X, Catechism of St. Pius X (1912), Q. 9-10.

Please let us know if you know of other references.

Rev. George Leo Haydock, Haydock Commentary (1811), note on Micheas 6:10.

St. John Chrysostom, Homily 23 on Romans (c. 390–397 AD), Ver. 7-8.